Presentation¶

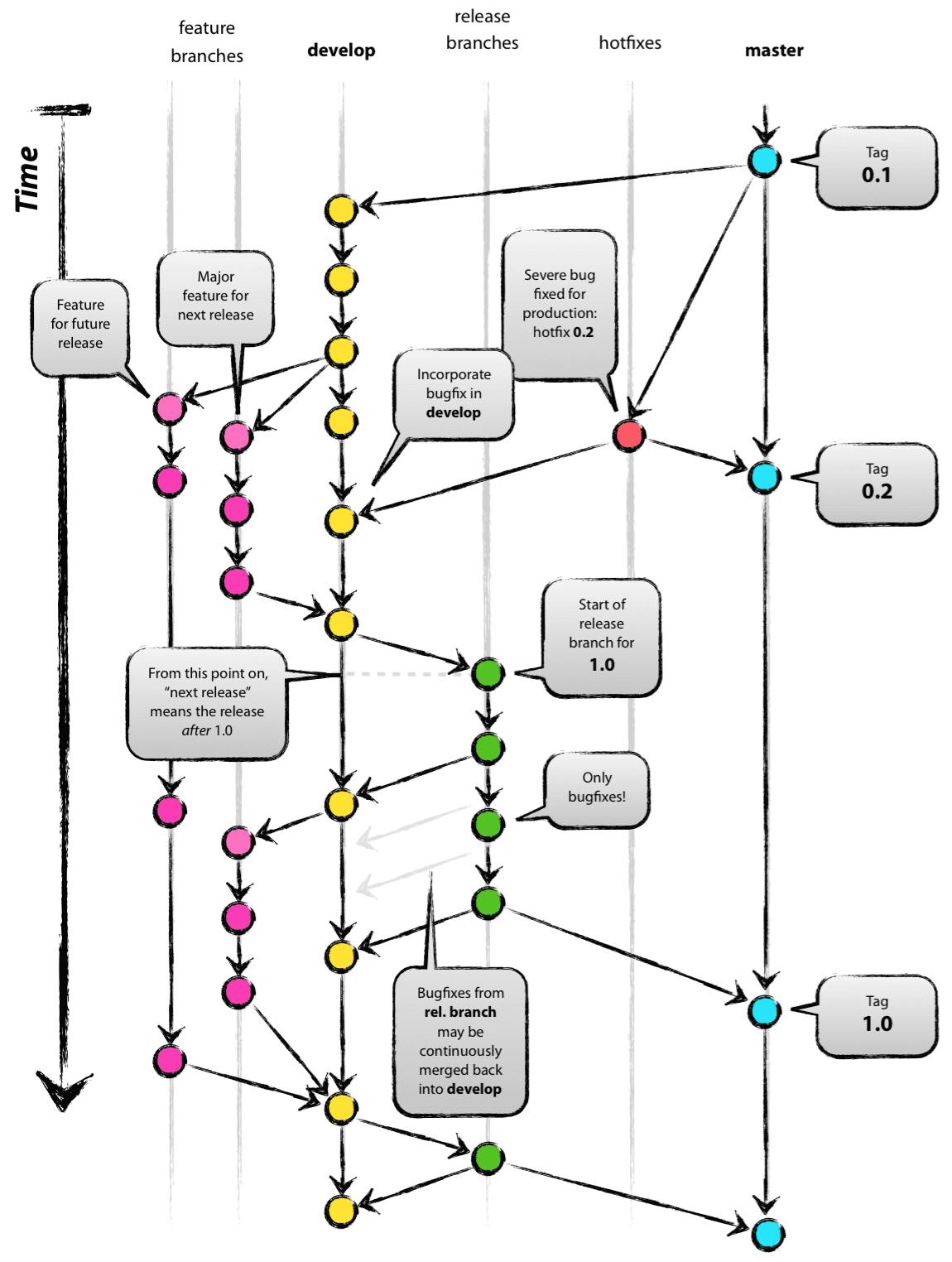

git-flow is a branching model, which come along with some documentation, and a git plugin to add command line facilities.

Keep in mind that it is just designed to get something standardized; all the background use standard git commands, you can achieve “manually” everything git-flow propose. It is just simplier to use, and it prevents to use the incorect branch, or to forget about merging somewhere.

It is not the goal of the present documentation to list pros and cons of this model, we’ll note that it is not designed to get long running support branches, it has been once something that would have been implemented; but it has not been done.

According to the semantic versionning rules:

- you’ll add

featuresonly for major or minor versions, - you’ll

releasemajor or minor versions, - you’ll

hotfixpatch versions.

Conventions¶

The present documentation assumes that:

- a

$sign will precede each command line instructions, - any term beetween

()before the$sign is the name of the current branch, - all is driven from the command line (I do not use any git GUI anyways).

Pre-requisites¶

In order the get the commands available; you’ll have to install the git-flow git plugin.

Most of Linux distributions have it in their repositories (so yum install git-flow or apt-get install git-flow would do the trick) or you can follow the installation instructions provided on the project wiki.

Many GIT software are aware of gitflow, or can be if you install a simple plugin; check their respective documentation.

If you use command line, there are numerous ways to get usefull informations displayed in your prompt. While this is not a pre-requisite, it can help you save time!

Working with Github¶

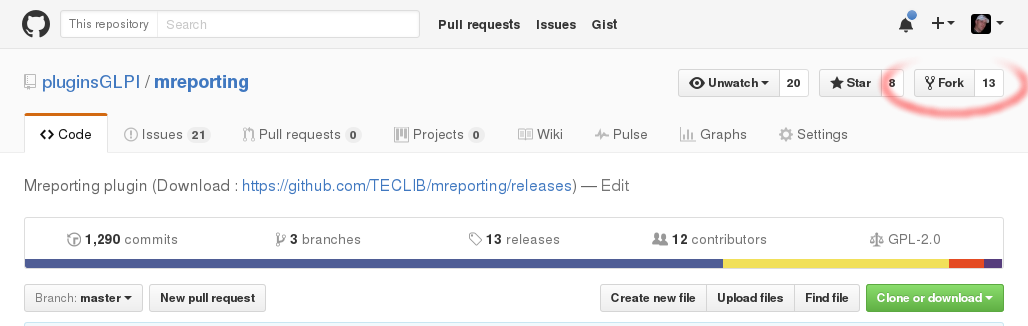

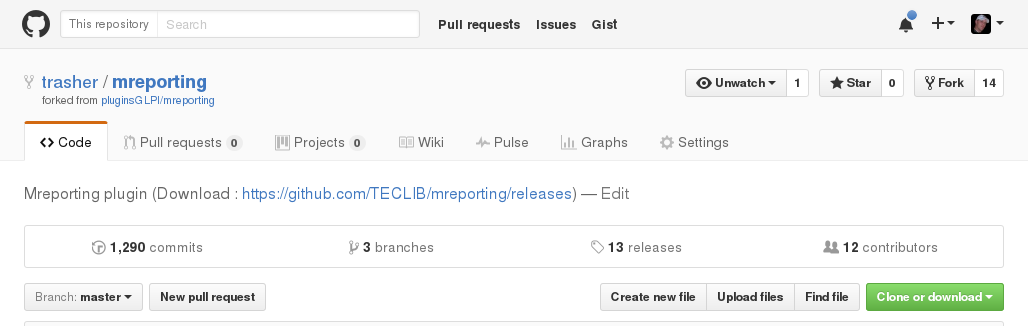

Each project will have a main repository hosted on Github. Even if you are part of the core developers, you will use the main repository only to push changes on the develop and master branches. All other branches will be created on a fork (use the eponym button at the top of the project - see below) you will create on your account.

From the main repository you’ve cloned the project to, add a new remote, let’s say naming as your github username (name does not matter, just remember what you choose, and stay consistent accross projects). Replacing {github_username} with your own username, run the following:

$ git remote add {github_username} git@github.com:{github_username}/mreporting.git

All branchs you will create that must be reviewed will be pushed to your fork.

Initialization¶

Initializing git-flow is quite simple, just clone the repository, go to the master branch and run:

Note

When you clone a git repository, the default branch will be checkout. In most cases, it will be master, but double check.

(master) $ git flow init

You can assume the default answer is correct for all questions. If the develop branch already exists, it will be used, the process will create it otherwise.

Not finished process¶

On some occasions, a git-flow command may not finish (in case of conflict, for exemple). This is really not a problem since its fully managed :)

If a git-flow process is stopped, just fix the issue and run the same command again. It will simply run all tasks remaining.

Note

To be sure everything worked as expected, always take a close look at the ouptut!

merge vs rebase¶

Should I merge or should I rebase? Well, it’s up to you!

Warning

Even if both solutions can be used, and you can choose one or another on some cases; always remember that a rebase can be destructive! Keep that in mind.

In facts, you can repair a rebase issue, but only on your local workspace (using reflog). Note this is really something you should not use if you’re not a git expert ;)

I do not want to feed any troll; both have pros and cons. My advice would be to avoid merge commits when it is not required. I’ll try to explain some common cases, and the way I do manage them with the few following examples…

You work on a feature; all that ends once squashed into one only commit. By default, the git-flow process will add your commit on the develop branch and will add an (empty) merge commit also. This one is really not required, it only make history less readable. If the merge commit is not empty, this begin to be more complicated; you probably miss a git flow feature rebase somewhere.

Conclusion: use rebase

You’ve added a hotfix, again one only commit. git-flow will create merge commits as well. For instance, I’m used to keep those commits, this is a visual trace in the history of what has been done regarding bug fixes.

Conclusion: use merge

You’ve finished a feature, just like someone else… But other side changes have already been pushed to remote develop. If you run (develop) $ git push, you will be informed that you cannot push because remote has changed.

I guess many will just run a (develop) $ git pull in that case, that will add a merge commit in your history. Those merge commits are really annonying searching in history, whether they’re empty or not. As an alternative, you can run (develop) $ git pull --rebase, this will prevent the merge commit.

Conclusion: use rebase

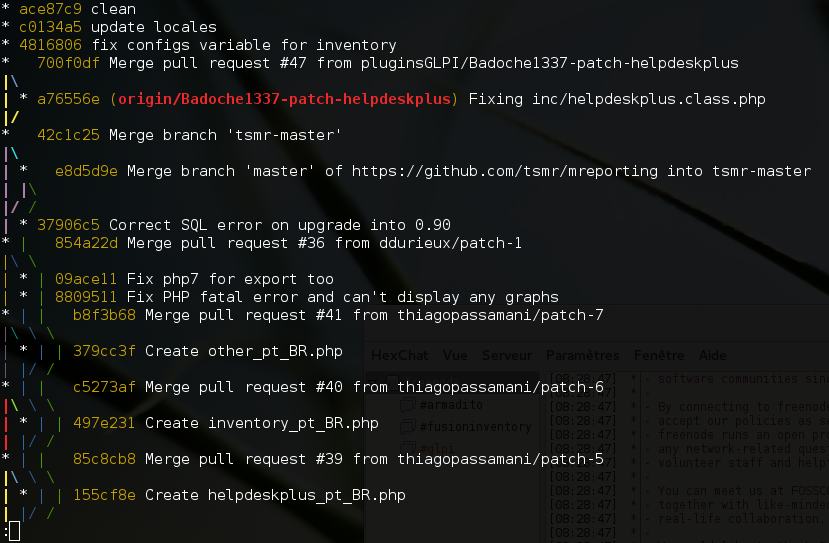

An example history (from the mreporting plugin).

Another example history (from the Galette project).